Introduction to Quantum

A Grand Unifying Theory

In his extensive treatise on Elastic membrane Theory, first published in 1892, AEH Love clarifies that the theory forms part of an overarching Theory about the constitution of matter itself, and the propagation of light. Introducing the work of Fresnel, he states ‘The theory of elasticity, and, in particular, the problem of the transmission of waves through an elastic medium (…means that) in the future {from 1821, the publication of Fresnel’s work} the developments of the theory of elasticity were to be closely associated with the question of the propagation of light. These two essential elements of Reality, matter defined as an elastic medium and the bending of light form the basis of our current (mis)understanding of Quantum Theory and so a clear guide through the historical roots, and the various minds that have been brought to bear on the subject over the centuries is a valuable exercise to make sure nothing has been overlooked that may be of value. Noting, of course that the fundamental perspective shift to the Earth being located around the Universal Axis is never considered.

As Love himself states, with regard to the progress of theory ‘..nothing that has once been discovered ever loses its value or has to be discarded; but the physical principles come to be reduced to fewer and more general ones, so that the theory is brought more into accord with that of other branches of physics, the same general dynamical principles being ultimately requisite and sufficient to serve as a basis for them all‘.

Engineers have been discarded from the world of theory by the self-imposed guardians of Natural Science, or Theoretical Physics as it is commonly known, and yet in more enlightened times, when any scientific study was referred to as Natural Philosophy, it is Engineers that have made the real breakthroughs; Love again ‘The… fact that most great advances in Natural Philosophy have been made by men who had a first-hand acquaintance with practical needs and experimental methods has often been emphasized; and, … is exemplified well in the history of our science‘

With the uncovering of Dr Viktor Lewe’s 1915 dissertation in 2023, it is clear that this proud tradition continued, so it is to all our disservice that the work is buried to hide atomic secrets. Lewe solves Gallileo’s Problem, and in so solving opens the door to a whole new perspective on Quantum observations, and of the Universe itself.

Love reaches an excellent conclusion on keeping an open mind to maintain scientific progress, ‘Although, in the case of Elasticity, we find frequent retrogressions on the part of the experimentalist, and errors on the part of the mathematician, chiefly in adopting hypotheses not clearly established or… discredited, in pushing to extremes methods merely approximate, in hasty generalizations, and in misunderstandings of physical principles, yet we observe a continuous progress in all the respects mentioned when we survey the history of the science’. An excellent mindset, do not be afraid to be wrong; progress to truth can only be gained by endeavour in ideas and courage in the face of peer pressure.

Noting the current crisis in both quantum and cosmology, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle falls into the category hypotheses not clearly established or… discredited? Certainly progress in Physics has been in notable decline since it was adopted as the unquestioned Foundation.

Love’s work is extensive, and involves so many of the mightiest minds from history, that it is possible to begin to see how a Grand Unifying Theory can finally evolve from this seemingly most mundane of concepts – what are the mechanisms that rupture a beam, and how can it be controlled for safe construction.

See Summary of Theory page for edited highlights.

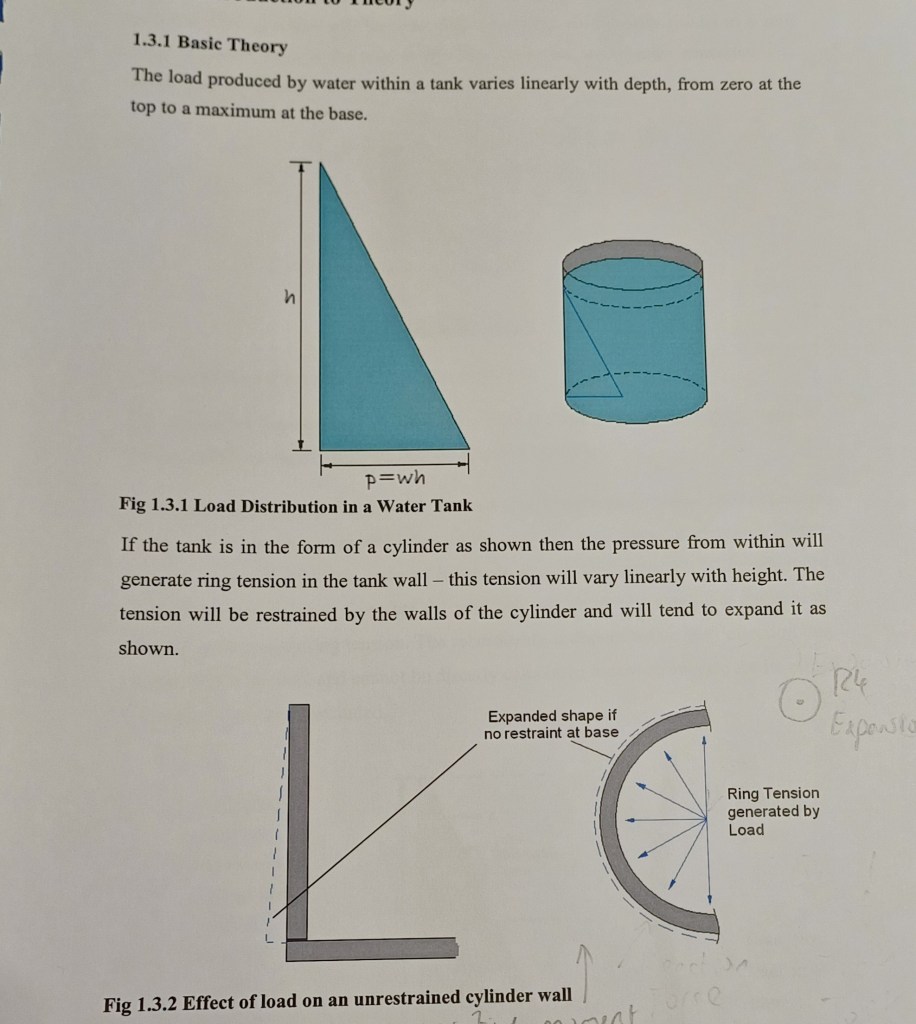

The Solution; Extract from ReynoldsBeng, 2008 thesis regarding Concrete Water Tank design practice:

The first accurate shell theory can be attributed to Love (1892). Love used the earlier work of Kirchoff on plate deformations to derive the basic equations that govern the behaviour of thin elastic shells based on four assumptions known as the Love-Kirchoff assumptions. These assumptions are still in use today despite attempts to refine them, although they are now called the Sanders-Koiter equations after some slight but significant modifications were made by these individuals.(19)

The differential equations as given by Love were not in a form suitable for practical analysis as they needed to be solved first resulting in Reissner’s 1908 work (see (21)) reducing the equations to two simultaneous, ordinary, second order differential equations specifically for cylindrical water tanks(19). In his contribution to Volume 5 of the 1915 Handbuch, Lewe produced the first attempt to provide a practical means for engineers to make use of Reissner’s analysis combining membrane, shearing and bending forces using charts and tables from which coefficients can be determined. The coefficients are inserted into equations with the specific tank design dimensions to produce the loading at different wall heights and allow design of the reinforcement steel.

and in 2024, I add the following, regarding the solution to Quantum;

The secret that is being kept from humanity by Science is that Lewe’s approach, whether accidental or by design, unveiled the Nuclear Force that binds matter and equally revealed its twin -the explosive Force of expansion and the propagation of light (and the corruption of the human psyche). That the Earth must be sited at the central axis of universal rotation is then but a simple step.

You are not allowed to know the following information;

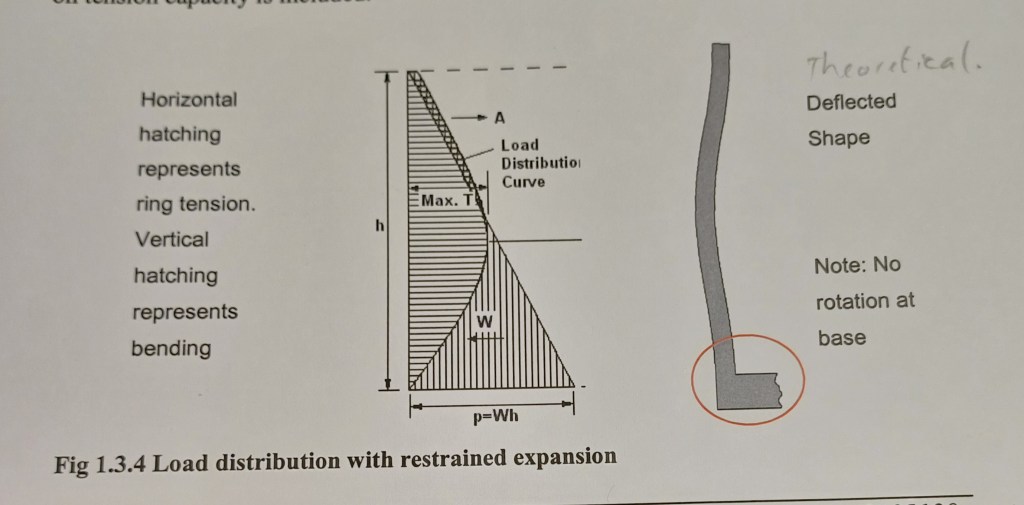

The leap forward Lewe makes in Quantum is through assuming that a cylinder of water is self-supporting, for one moment in time. By assuming a fixed wall construction at the base, with no sliding or rotation, a sliver of this wall can now be analysed as a particle thin column, subject to buckling from self-weight, or as a beam supported at either end (if assumed horizontal), subject only to self-weight loading. The shape taken by the water will be as Fig 1.3.4 (from Reynolds BEng 2008 thesis) below, and the competing and combining forces of tension and bending will be as shown in fig on left.

The tank sidewall is imagined as non-existent, just a standing wave of water, subject to self-weight only (ie the effect of gravity causing buckling) and the forces within this (now vertical, but otherwise analysed identically to a horizontal) beam can be analysed using the mathematical tool of matrix calculus. Rest Time is therefore assumed, T=0, for the load derivation process, and mass is also ignored by assuming infinitessimal particle scale, leaving behind only the momentum of the water, m/s2 creating the property of mass, g.

A meniscus is assumed, just as observed at the surface (the boundary condition where acceleration within the body of water becomes pure vector change due to gravity. Acceleration becomes a constant [but variable value c m/s] velocity with angular momentum) so we can derive angular momentum alone, and comprehend gravity as tidal Love Waves (see also below) within, and on the surface of, the structure of a spherical water molecule).

The assumed standing meniscus is additionally subject to bending forces from the weight of its own mass. The forces are infinitely both nonparellel ( and ultraparallel) translations in a 3-dimensional plane (x,y,z) and with 3 further freedoms of movement of rotation (roll, yaw and pitch) within each molecule of the standing meniscus and are therefore definitely statically indeterminate in terms of bending analysis. The method of calculating resultant of all forces in such a system is extremely complex, and was seemingly beyond even the most celebrated of genii, but Lewe shows in his 1915 Dissertation that Matrix Calculus is the tool by which the load of momentum of Nuclear Force can be quantised into a measurable, but meaningful, entity, and his companion Handbuch article demonstrates a practical application in construction of concrete water tanks (and by extension, all shell structures). The momentum is the Force of the bending moment of the limit of Entropy within, not about, the centroid, measured as Sm4, and defines the diameter of a water molecule, and so the binding force of Maxwell’s demon is revealed. The acceleration of Entropy is arrested at the point where a moment, of measurable duration h seconds, is created by infinite vector change at the surface of a water molecule. This system describes every piece of matter in the universe and the behaviour of Light, to create Time.

Creation Moment

Both as a body, and as motion within an individual molecule, the momentum of water has turbulent flow (which explains Heisenberg‘s connection, using same technique of coefficient tables) but the motion of turbulence creates laminar flow, perpendicular to the creating force; a balancing expansive force of equal and opposite reactions about a turbulent zero point singularity.

Where T=0 (then T=infinity) and water exists, of volume m3, with a moment of force N (torque) of potential distance, m, then cavitation will occur (sogen Reynolds Numbers define the point of cavitation); within the body of water, a bubble is formed with a vacuum of negative pressure relative to its environment (the water). The lighter elements of the water molecule composite, the gases, will be attracted to this void, and will separate into Hydrogen and Oxygen. The reaction between the two gases is explosive, creating heat and light and detritus within the bubble, which causes expansion. Given that within the bubble, time is infinite, limited only by bubble duration then, if the energy created from the explosive force of the gases is greater than the energy that created the cavitation, the illuminated bubble will sustain itself for infinite time (when observed and measured from within) although may actually only last for one moment duration, measurable as Planck’s (not) Constant, 6.62607015 x 10-34 seconds (no I didn’t look it up). The expansion within the bubble has a centroid from which to be relative, and the detritus gathers lives there, being heavier than the gases. The effect of the expansion acceleration is then experienced by the detritus at the centre of the sphere as an opposite reaction, but with nowhere to go, because it is at the centre, surrounded by expansive force, so the detritus gains density, relative to the expansion force. The created light is bent by the restraint at the boundary conditions causing effects on the detritus, such as it experiencing ‘weight’ and being aware of the light (that it itself sustains) and inhabits, and eventually being able to record and measure its properties, once it becomes animated, through the awareness of difference in the Quality of the Light, it can exercise choice. Does the detritus choose to turn towards, or away from, the light. Does it choose a Positive or Negative Moment of time?

The Power of the Bending Force that creates the Light that generates the Momentum that both carries, and turbulently modifies, the Power, from one moment of time to the next is centred at the centre of the system of course. The centre of Reality itself is The Earth, the Infinite Axis of the Cosmos; a 2-dimensional dot point balance of pure force in motion.

Thanks for the Information, Science. Why have I never heard of Dr Dr Viktor Lewe?

Love (1892) Rules

It all begins with Love, AEH, 1892

[Wikipedia extracts]. – [Augustus Edward Hough Love (1863 -1940) was a British mathematician famous for his work on the mathematical theory of elasticity. He was very much a man of practical application, and interested in the Earth and its place in the cosmos; he published works on wave propagation and the structure of the Earth. Love also contributed to the theory of gravitational, or tidal locking and introduced the parameters known as Love numbers, used in problems related to Earth tides, which describe the variation of the planet’s elastic properties under the tidal deformation of the gravitational attraction of the Moon and Sun. In Some Problems of Geodynamics he developed a mathematical model of surface waves known as Love waves. The Love wave is a result of the interference of many shear waves (S-waves) guided by an elastic layer, which is welded to an elastic half space on one side while bordering a vacuum on the other side. {effectively a single-sided surface}

Notice in the diagram that the Love Waves travel in alternating fashion. This motion occurs at particle scale forming a horizontal line perpendicular to the direction of propagation (i.e. are transverse waves). Moving deeper into the material, motion can decrease to a “node” and then alternately increase and decrease as one examines deeper layers of particle.

In A Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, 1892, Love states ‘The Mathematical Theory of Elasticity is occupied with an attempt to reduce to calculation the state of strain, or relative displacement, within a solid body which is subject to the action of … a state of slight internal relative motion, and with endeavours to obtain results which shall be practically important in applications to architecture, engineering, and all other useful arts in which the material of construction is solid”.

So Love is presenting an engineering assessment of elastic properties of solids at particle scales. Very much theoretical, in terms of finite analysis, but practical in application to consider why structures fail and, through calculation, prevent it. As Love puts it ‘to devise means for effecting economies in engineering constructions or to ascertain the conditions in which structures become unsafe’. At the end of his introduction to his Treatise, Love gives us a hint perhaps of the reason Lewe himself became an engineer; ‘The… fact that most great advances in Natural Philosophy have been made by men who had a first-hand acquaintance with practical needs and experimental methods has often been emphasized; and, … is exemplified well in the history of our science‘.

In 1915, after 11 years as a consulting engineer, Dr sc.nat Viktor Lewe presents his method of analysing the motion of a node at particle scale – Matrix Calculus. His companion article in der Handbuch (in 1923, ascribed to Dr.Ing Dr V Lewe) fits the brief for practical application for engineers, but it his Dissertation Theory that completes the advance in Love’s ‘Natural Philosophy’ to prove the existence of absolute motion at the heart of the Nuclear Force of all substances, and, unfortunately, instead of being a new dawn for Engineering, opens the door for a corrupted Scientific century of atomic weapons and energy.

A Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, Love (1892)

There is an excellent summary of Love’s Mathematical Treatise on Wikiquotes giving a detailed historical summary of the theory of elasticity, which is actually a summary of the theories of everything; matter, light’ and the nature of reality. I update with information unknown to Love at the time with regard to DaVinci and added comment as appropriate viewed in context of Lewe’s solution in 1915. The Wikiquotes summary of the Treatise is in bold, [some information lifted from Wikipedia on the scientists and engineers referenced by Love are included in order of introduction in square brackets] and Reynolds BEng commentary {in italics}.

A Treatise on the Mathematical Theory of Elasticity, by Augustus Edward Hough Love, is a classic two volume text, each separately published in the years 1892 and 1893 respectively. The second edition, published in 1906 {same date as Lewe’s Physics Doctorate. A copy has not been sourced so references cannot be checked, but Love 1892 would be the seminal work, and I would anticipate it being referenced by Lewe in 1906} is a fundamental rewrite of the entire previous two volume set. The following quotes are from the second edition, unless otherwise noted.

Preface to the 1st edition (1892)

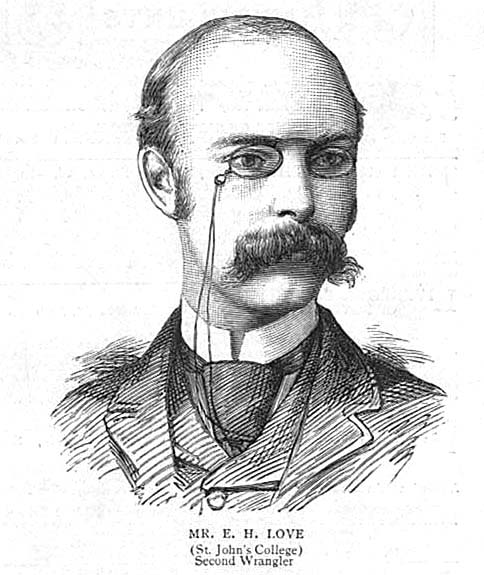

The present treatise is the outcome of a suggestion made to me some years ago by Mr R. R. Webb that I should assist him in the preparation of a work on Elasticity. He has unfortunately found himself unable to proceed… and I have therefore been obliged to take upon myself the whole of the… responsibility. I wish to acknowledge… the debt that I owe to him as a teacher of the subject, as well as… for many valuable suggestions… [ Love won a scholarship to St John’s College, Cambridge in 1881 where he was at first undecided whether to study classics or mathematics. His successful progress (he was placed Second Wrangler)[5] vindicated his choice of mathematics {Webb would have been one of Love’s lecturers in St John’s, one can imagine it was perhaps Webb who persuaded Love of his mathematical talents but that he always maintained an interest in practical application of theory, see his conclusion to his treatise}

[Robert Rumsey Webb (1850 – 1936) was a successful coach for the Cambridge Mathematical Tripos. Webb coached 100 students to place in the top ten wranglers from 1865 to 1909, a record second only to Edward Routh.

Webb produced memorable lectures on the theory of elasticity and became a Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society on 18 November 1879. As senior wrangler himself, when Andrew Warwick reviewed the record for his book Masters of Theory {a title worth having}, his tally of top ten wranglers placed Webb second. His “real memorial lies in the careers of his pupils.”]

The division of the subject adopted is that… by Clebsch in his classical treatise, where a clear distinction is drawn between exact solutions for bodies all whose dimensions are finite and approximate solutions for bodies some of whose dimensions can be regarded as infinitesimal. {linking Real Time to Simultaneous Time} The present volume contains the general mathematical theory of the elastic properties of the first class of bodies, and I propose to treat the second class in another volume.

Reference: Alfred Clebsch, Theorie der Elasticität fester Körper [Theory of Elasticity of Solid Bodies] (1862)

[Rudolf Friedrich Alfred Clebsch (1833 – 1872) was a German mathematician who made important contributions to algebraic geometry and invariant theory. He was habilitated at Berlin {as was Lewe in 1920} He subsequently taught in Berlin and Karlsruhe. His collaboration with Paul Gordan in Giessen led to the introduction of Clebsch–Gordan coefficients for spherical harmonics, which are now widely used in quantum mechanics.]

At Mr Webb‘s suggestion, the exposition of the theory is preceded by an historical sketch of its origin and development. Anything like an exhaustive history has been rendered unnecessary by the work of the late Dr Todhunter as edited by Prof. Karl Pearson but it is hoped that the brief account given will at once facilitate the comprehension of the theory and add to its interest.

Reference is made to Isaac Todhunter, A History of the Theory of Elasticity and of the Strength of Materials Vol. 1 (1886) & Vol. 2 (1893) ed., Karl Pearson. [This was an unfinished work, edited and published posthumously by Karl Pearson]

In the analysis of strain I have thought it best to follow Thomson {Lord Kelvin} and Tait‘s Natural Philosophy, beginning with the geometrical or rather algebraical theory of finite homogeneous strain, and passing to the physically most important case of infinitesimal strain. {explaining that Strain can be analysed using geometry and algebra, a technique going back to Pythagoras and beyond, but (he explains later) that a Theoretical Physics must necessarily be used to understand the same property in quantum, the arena of the infinitessimally small}

[William Thomson (1824–1907), 1st Baron Kelvin, often referred to simply as Lord Kelvin, was an Irish mathematical physicist.

‘Mathematics is the only true metaphysics.’ As quoted by Silvanus Phillips Thompson, The Life of William Thomson, Baron Kelvin of Largs (1910) Vol. 2, p. 1124

‘Do not imagine that mathematics is hard and crabbed, and repulsive to common sense. It is merely the etherealization of common sense.‘ Quoted in Life of Lord Kelvin (1910) by Silvanus Phillips Thompson

‘Now I think hydrodynamics is to be the root of all physical science, and is at present second to none in the beauty of its mathematics.‘ In a letter addressed to George Stokes dated December 20, 1857, as quoted in Fluid Mechanics in the Next Century (1996), by Mohamed Gad-el-Hak and Mihir Sen.

‘…the water flow down by a gradual natural channel, its potential energy is gradually converted into heat by fluid friction…has led to the greatest reform that physical science has experienced since the days of Newton. From that discovery, it may be concluded with certainty that heat is not matter, but some kind of motion among the particles of matter; a conclusion established, it is true, by Sir Humphrey Davy and Count Rumford at the end of last century, but ignored by even the highest scientific men during a period of more than forty years’. Thompson, 1884]

{Here in 2024, Hookes Law still stands, but the idea that thermodynamics has any kind of metaphysical quality have been firmly rejected, although note, not disproven.}

[Peter Guthrie Tait FRSE (1831 – 1901) was a Scottish mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook Treatise on Natural Philosophy, which he co-wrote with Lord Kelvin, and his early investigations into knot theory which contributed to the eventual formation of topology as a mathematical discipline. His name is known in graph theory mainly for Tait’s conjecture on cubic graphs. He is also one of the namesakes of the Tait–Kneser theorem on osculating circles.]

The discussion of the stress-strain relations rests upon Hooke’s Law as an axiom generally verified in experience, and on Sir W. Thomson[‘s] thermodynamical investigation of the existence of the energy-function.

The theory of elastic crystals adopted is that which has been elaborated by the researches of F. E. Neumann and W. Voigt. {Crystal behaviour, heat motion, electrodynamics and time dilation}

[F.E Neumann (1798-1885) Student of Theology, studied crystallography, professor of Mineralogy and Physics ‘…with his deduction of the elastic constants (on which the optical properties depend) Neumann employed the assumption that the symmetry of the elastic behaviour of a crystal was equal to that of its form. In other words, he assumed that the magnitudes of the components of a physical property in symmetric positions are equivalent. This assumption substantially reduced the number of independent constants and greatly simplified the elastic equations.’]

[Woldemar Voigt (1850-1915) Student of Neumann, Head of Mathematical Physics, Gottingen (succeeded by Peter Debye). Hermann Minkowski said in 1908 that the transformations which play the main role in the principle of relativity were first examined by Voigt in 1887. Also Hendrik Lorentz (1909) is on record as saying that he could have taken these transformations into his theory of electrodynamics, if only he had known of them, rather than developing his own. It is interesting then to examine the consequences of these transformations from this point of view. Lorentz might then have seen that the transformation introduced relativity of simultaneity, and also time dilation]

[In physics, the ‘relativity of simultaneity’ is the concept that distant simultaneity – whether two spatially separated events occur at the same time – is not absolute, but depends on the observer’s reference frame. This possibility was raised by mathematician Henri Poincaré in 1900, and thereafter became a central idea in the special theory of relativity. According to the special theory of relativity introduced by Albert Einstein, it is impossible to say in an absolute sense that two distinct events occur at the same time if those events are separated in space. If one reference frame assigns precisely the same time to two events that are at different points in space, a reference frame that is moving relative to the first will generally assign different times to the two events (the only exception being when motion is exactly perpendicular to the line connecting the locations of both events)]

The conditions of rupture {the loading on a beam at the moment of failure} or rather of safety of materials are as yet so little understood that it seemed best to give a statement of the various theories that have been advanced without definitely adopting any of them.

In most of the problems considered in the text Saint-Venant‘s “greatest strain” theory {yielding will occur when the maximum principal strain just exceeds the strain at the tensile yield point in either simple tension or compression} has been provisionally adopted. In connexion with this theory I have endeavoured to give precision to the term “factor of safety“.

[Saint-Venant (1797-1886) Mechanician, mathematician, civil engineer, hydraulic engineering, developed his own vector calculus]

Among general theorems I have included an account of the deduction of the theory from Boscovich‘s point-atom hypothesis. This is rendered necessary partly by the controversy that has raged round the number of independent elastic constants, and partly by the fact that there exists no single investigation of the deduction in question which could now be accepted by mathematicians.

[R.J Boscovich (1711-1787) physicist, astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, diplomat, poet, theologian, Jesuit priest. From Leon M. Lederman, p.103 The God Particle: If the Universe is the Answer, what is the Question? (1993)) ‘Roger Joseph Boscovich … speculated that …classical law must break down altogether at the atomic scale, where the forces of attraction are replaced by an oscillation between attractive and repulsive forces. An amazing thought for a scientist in the eighteenth century. Boscovich also struggled with the old action-at-a-distance problem. Being a geometer more than anything else, he came up with the idea of “fields of force” to explain how forces exert control over objects at a distance. But wait, there’s more! Boscovich had this other idea, one that was real crazy for the eighteenth century (or perhaps any century). Matter is composed of invisible, indivisible a-toms, he said (but) Here’s the good part: Boscovich said these particles had no size; that is, they were geometrical points … a point is just a place; it has no dimensions. {this is an excellent description of ‘infinitessimal’}

and from Philip Ball, Critical Mass: How One Thing Leads to Another (2006) – if all the world is just atoms in motion and collision, then an all-seeing mind “could, from a continuous arc described in an interval of time, no matter how small, by all points of matter, derive the law [that is, a universal map] of forces itself … Now, if the law of forces were known, and the position, velocity and direction of all the points at any given instant, it would be possible for a mind of this type to foresee all the necessary subsequent motions and states, and to predict all the phenomena that necessarily followed from them.]

{Contrast Boscovich’s ambition for Physics with Heisenberg’s Uncertainty, where either momentum or position can be known, but not both, and that this theory ‘warrants no further modification’, and yet there is promise in Elastic Theory to be able to predict ALL phenomena that necessarily follow. Lewe shows that it is possible to determine position, velocity and direction, so Science likely already has the power to control the future, using Quantum Computers and Data Biostatistics (see Karl Pearson below)}

[With regard to] Saint-Venant‘s theory of the equilibrium of beams… In spite of the work of Prof. Pearson it seems not yet to be understood by English mathematicians that the cross-sections of a bent beam do not remain plane. {Look at the diagram of Love Wave above. He is saying that there is an oscillating twisting force in a loaded beam. Lewe completes this idea by proving the ‘twist’ of competing forces created at the point of rupture} The old-fashioned notion of a bending moment proportional to the curvature resulting from the extensions and contractions of the fibres is still current. Against the venerable bending moment the modern theory has nothing to say, but it is quite time that it should be generally known that it is not the whole stress [stress is a physical quantity that describes forces present during deformation. For example, an object being pulled apart, such as a stretched elastic band, is subject to tensile stress and may undergo elongation. An object being pushed together, such as a crumpled sponge, is subject to compressive stress and may undergo shortening. The greater the force and the smaller the cross-sectional area of the body on which it acts, the greater the stress. Stress has dimension of force per area, with SI units of newtons per square meter (N/m2) or pascal (Pa)], and that the strain [defined as relative deformation, compared to a reference position configuration] does not consist simply of extensions and contractions of the fibres. In explaining the theory I have followed Clebsch‘s mode of treatment, generalising it so as to cover some of the classes of aeolotropic bodies [a body or substance, having physical properties (e.g., electric conductivity, refractive index) that depend on the direction in which they are measured] treated by Saint-Venant.

[Karl Pearson (1857-1936) English mathematician and biostatistician. Proposes a theory of probability allowing a measure of uncertainty – ‘The purpose of the mathematical theory of statistics is to deal with the relationship between 2 or more variable quantities without assuming that one is a single-valued mathematical function of the rest. The statistician does not think a certain x will produce a single-valued y; not a causative relation but a correlation. The relationship between x and y will be somewhere within a zone and we have to work out the probability that the point (x,y) will lie in different parts of that zone. The physicist is limited and shrinks the zone into a line. Our treatment will fit all the vagueness of biology, sociology, etc. A very wide science.]

[We] are occupied with the principal analytical problems presented by elastic theory. The theory leads in every special case to a system of partial differential equations, and the solution of these subject to conditions given at certain bounding surfaces is required. The general problem is that of solving the general equations with arbitrary conditions at any given boundaries. In discussing this problem I have made extensive use of the researches of Prof. Betti of Pisa, whose investigations are the most general that have yet been given…

[Enrico Betti Glaoui (1823 –1892) was an Italian mathematician, now remembered mostly for his 1871 paper on topology {see also Tait} concerned with the properties of a geometric object that are preserved under continuous deformations, such as stretching, twisting, crumpling, and bending; that is, without closing holes, opening holes, tearing, gluing, or passing through itself. He later worked in the area of theoretical physics and Italian State politics]

The case of a solid bounded by an infinite plane and otherwise unlimited is investigated on the lines laid down by Signor Valentino Cerruti, whose analysis is founded on Prof. Betti’s general method, and some of the most important particular cases are worked out synthetically by M. Boussinesq‘s method of potentials. In this connexion I have introduced the last-mentioned writer’s theory of “local perturbations”, a theory which gives the key to Saint-Venant‘s “principle of the elastic equivalence of statically equipollent systems of load”.

[Equipolent

[Valentino Cerruti (1850 –1909) was an Italian mathematician, physicist and politician. At the School of Engineering of the University of Rome in 1877 he won a competition and was promoted to professor of rational mechanics, a role he held for the rest of his life. His research mainly concerned the theory of elasticity and mathematical physics. In his career he was also rector of the University of Rome

and is also considered the true founder of the Central Library of the Faculty of Engineering of the University of Rome, which he expanded to make it the most important in Italy]

[Joseph Valentin Boussinesq (1842 – 1929) was a French mathematician and physicist who made significant contributions to the theory of hydrodynamics, vibration, light, and heat. From 1872 to 1886, he was professor at Faculty of Sciences of Lille, lecturing differential and integral calculus, from1896 to his retirement in 1918, he was professor of mechanics at Faculty of Sciences of Paris.

In 1897, he published Théorie de l’écoulement tourbillonnant et tumultueux des liquides (“Theory of the swirling and agitated flow of liquids”), a work that greatly contributed to the study of turbulence and hydrodynamics. The word “turbulence” was never used by Boussinesq. He used sentences such as “écoulement tourbillonnant et tumultueux” (vortex or tumultuous flow). The first mention of the word “turbulence” in French or English scientific fluid mechanics literature (the word “turbulence” existed in other context) can be found in a paper by Lord Kelvin in 1887. Reference: Joseph Valentin Boussinesq, Application des potentiels à l’étude de l’équilibre et du mouvement des solides élastiques (1885)]

The student without previous acquaintance with the subject is advised in all cases to provide the required proofs. It is hoped that he will not then fail to understand the subject for lack of examples, nor waste his time in mere problem grinding.

Historical Introduction

The Mathematical Theory of Elasticity is occupied with an attempt to reduce to calculation the state of strain, or relative displacement, within a solid body {note Lewe’s 1915 dissertation is called The Application of Matrix Calculus to Continuous Beams and Framed Structures, which is a calculation method of relative displacement in a solid body subjected to bending} which is subject to the action of an equilibrating system of forces, or is in a state of slight internal relative motion, and with endeavours to obtain results which shall be practically important in applications to architecture, engineering, and all other useful arts in which the material of construction is solid. {Love’s intention is for his theory to be used in the practical design of engineering structures. This is Lewe’s stated intent also in his 1915 Handbuch method, to devise a method of calculation for the ‘mathematically less-trained’. Love defines an elastic body as ‘subject to the action of an equilibrating system of forces, or is in a state of slight internal relative motion‘. Lewe shows that at infinitesimal scale, where dot points have only a place, not a dimension, the balancing forces create an oscillating twisting motion. It is this motion that defines the elastic properties of the material, and therefore its strength}

Alike in the experimental knowledge obtained, and in the analytical methods and results, nothing that has once been discovered ever loses its value or has to be discarded; but the physical principles come to be reduced to fewer and more general ones, so that the theory is brought more into accord with that of other branches of physics, the same general dynamical principles being ultimately requisite and sufficient to serve as a basis for them all. {Seeking a unifying principle for all branches of Physics}

[A]lthough, in the case of Elasticity, we find frequent retrogressions on the part of the experimentalist, and errors on the part of the mathematician, chiefly in adopting hypotheses not clearly established or… discredited, in pushing to extremes methods merely approximate, in hasty generalizations, and in misunderstandings of physical principles, yet we observe a continuous progress in all the respects mentioned when we survey the history of the science from the initial enquiries of Galileo {now traced further back to DaVinci} to the conclusive investigations of Saint-Venant and Lord Kelvin.

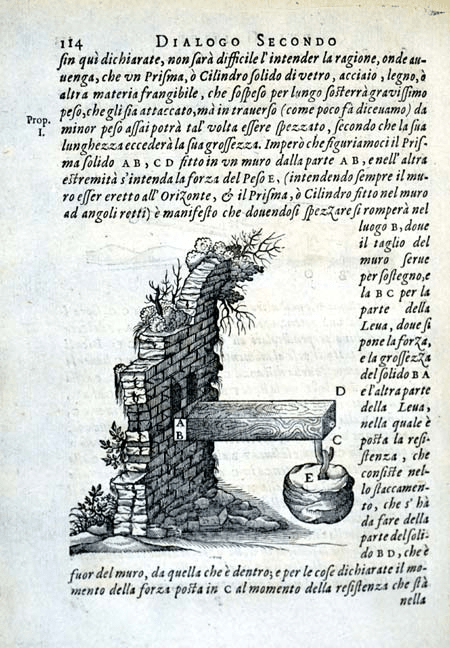

The first mathematician to consider the nature of the resistance of solids to rupture was Galileo. Although he treated solids as inelastic, not being in possession of any law connecting the displacements produced with the forces producing them, or of any physical hypothesis capable of yielding such a law, yet his enquiries gave the direction which was subsequently followed by many investigators.

{Extract on earliest known work is from The elastica: a mathematical history Raph Levien August 23, 2008

Jordanus de Nemore—13th century

In the recorded literature, the problem of the elastica was first posed in De Ratione Ponderis by Jordanus

de Nemore (Jordan of the Forest), a thirteenth century mathematician. Proposition 13 of book 4 states

that “when the middle is held fast, the end parts are more easily curved.” He then poses an incorrect

solution: “And so it comes about that since the ends yield most easily, while the other parts follow more

easily to the extent that they are nearer the ends, the whole body becomes curved in a circle.” In

fact, the circle is one possible solution to the elastica, but not to not for the specific problem posed. Even

so, this is a clear statement of the problem, and the solution (though not correct) is given in the form of

a specific mathematical curve. It would be several centuries until the mathematical concepts needed to

answer the question came into existence.}

{Love was not aware of Leonardo Da Vinci’s work that predates Galileo but it is clear that Da Vinci had already completed the work on balancing the stress/strain relationship. In The history of the theory of beam bending – Part 1 (32) we learn ; ‘Galileo Galilei is often credited with the first published theory of the strength of beams in bending, but with the discovery of “The Codex Madrid” in the National Library of Spain in 1967 it was found that Leonardo da Vinci’s work (published in 1493) had not only preceded Galileo’s work by over 100 years, but had also, unlike Galileo, correctly identified the stress and strain distribution across a section in bending‘

In spite of Leonardo’s accurate appreciation of the stresses and strains in a beam subject to bending, he did not provide any way of assessing the strength of a beam, knowing its dimensions, and the tensile strength of the material it was made of.” {ie did not produce a method of calculating strain}

The relevant page is Folio 84, reproduced below and whole document is available from Cornell University

Translation of notebook entry; ‘Therefore, the centre of its height has become much like a balance for the sides. And the ends of those lines draw as close at the bottom as much as they draw away at the top. From this you will understand why the centre of the height of the parallels never increases in ‘ab’ nor diminishes in the bent spring at ‘co.’”{Note that this quote is lifted from a full translation which was available in the American Society of Mechanical Engineers magazine (in 2008), but the in the link in the webpage that should lead to the page is not functioning, suggesting this article has been deleted, which is unhelpful, especially since translations in English are rare according to this source}

[Galileo] endeavoured to determine the resistance of a beam, one end of which is built into a wall, where the tendency to break arises from its own or an applied weight; and he concluded that the beam tends to turn about an axis perpendicular to its length, and in the plane of the wall. This problem, and, in particular, the determination of this axis is known as Galileo’s problem.

{Many mathematicians before Galileo had dealt with the problem of statics – how forces are transmitted by structural members. Galileo proposed a new science, the study of the strength of materials (Dr Lewe’s academic field, 1920 to 1936), that considered how the size and shape of structural members affects their ability to carry and transmit loads. He discovered that as the length of a beam increases, its strength decreases, unless you increase the thickness and breadth at an even greater rate. You cannot, therefore, simply double or triple the dimensions of a beam, and expect it to carry double or triple the load. This led Galileo to recognize what we now call the scaling problem – there are limits to how big nature can make a tree, or an animal, for beyond a certain limit, the branches of the tree or the limbs of the animal, will break under their own weight}. His illustration of a cantilever beam demonstrates that the breaking force on a beam increases as the square of its length.

{An interesting discussion on ‘Galileos’ problem’ which explains the principles can be found here (33)}

The two great landmarks are the discovery of Hooke’s Law in 1660, and the formulation of the general equations by Navier in 1821.

Hooke’s Law provided the necessary experimental foundation for the theory. [The modern theory of elasticity generalizes Hooke’s law to say that the strain (deformation) of an elastic object or material is proportional to the stress applied to it. However, since general stresses and strains may have multiple independent components, the “proportionality factor” may no longer be just a single real number, but rather a linear map (a tensor) that can be represented by a matrix of real numbers] When the general equations had been obtained, all questions of the small strain of elastic bodies were reduced to a matter of mathematical calculation.

Hooke and Mariotte occupied themselves with the experimental discovery of what we now term stress-strain relations. Hooke gave in 1678 the famous law of proportionality of stress and strain which bears his name, in the words “Ut tensio sic vis; that is, the Power of any spring is in the same proportion with the Tension thereof.” By “spring” Hooke means… any “springy body,” and by “tension” what we should now call “extension,” or, more generally, “strain.” This law he discovered in 1660, but did not publish until 1676, and then only under the form of an anagram, ceiiinosssttuu. This law forms the basis of the mathematical theory of Elasticity {Love’s}

[Robert Hooke FRS (1635 – 1703) was an English polymath, a physicist (“natural philosopher”), astronomer, geologist, meteorologist and architect. He is credited as one of the first scientists to explore living things at microscopic scale (in 1665), using a compound microscope that he designed. In recent times, he has been called “England’s Leonardo“ {Interesting that Hooke, as Da Vinci does, uses cryptic means to express his discoveries}

{Edme Mariotte (1620 – 1684) was a French physicist and priest (abbé). He is particularly well known for formulating Boyle’s law independently of Robert Boyle.]

{From (32) the article about DaVinci’s insights ‘Due to the incorrect assumptions of uniform stress across the section and rotation about the base of the section, Galileo’s result was three times higher than the correct value for a brittle material which has approximately linear behaviour up to its failure load. The disparity between Galileo’s calculations and actual breaking loads did not go unnoticed, and in 1686 Edme Mariotte’s alternative approach was published. Mariotte initially retained Galileo’s position of the axis or rotation, but proposed a triangular stress distribution, varying from the failure stress at the top to zero at the base. He then proposed (without proof) that the neutral axis should be at the centre of the section, but also introduced an error in his working resulting in the section modulus being double its correct value, as it would be if the neutral axis were at the base of the section as he had initially assumed.‘

The correct formula was eventually derived by Antoine Parent in 1713 who correctly assumed a central neutral axis and linear stress distribution from tensile at the top face to equal and opposite compression at the bottom, thus deriving a correct elastic section modulus of the cross sectional area times the section depth divided by six. Unfortunately Parent’s work had little impact, and it was many more years before scientific principals were regularly applied to the analysis of the strength of beams in bending}

{Interesting that Love does not reference Antoine Parent}

[Antoine Parent (1666 – 1716) was a French mathematician, who wrote in 1700 on analytical geometry of three dimensions. His works were collected and published in three volumes at Paris in 1713.

Parent had the idea to represent any surface by means of an equation between the three coordinates to any of its points. He derived the correct formula for bending of cantilever beams. He correctly assumed a central neutral axis and linear stress distribution from tensile at the top face to equal and opposite compression at the bottom, thus deriving a correct elastic section modulus of the cross sectional area times the section depth divided by six. Parent’s work had little impact, and it was many more years before scientific principles were regularly applied to the analysis of the strength of beams in bending’]

Hooke does not appear to have made any application of [his law] to the consideration of Galileo’s problem. This application was made by Mariotte, who in 1680 enunciated the same law independently. He remarked that the resistance of a beam to flexure arises from the extension and contraction of its parts, some of its longitudinal filaments being extended, and others contracted. He assumed that half are extended, and half contracted. His theory led him to assign the position of the axis, required in the solution of Galileo’s problem, at one-half the height of the section above the base.

In the interval between the discovery of Hooke’s law and that of the general differential equations of Elasticity by Navier, the attention of those mathematicians who occupied themselves with our science was chiefly directed to the solution and extension of Galileo’s problem, and the related theories of the vibrations of bars and plates, and the stability of columns.

[Claude-Louis Navier (1785 – 1836). Navier formulated the general theory of elasticity in a mathematically usable form (1821), making it available to the field of construction with sufficient accuracy for the first time. In 1819 he succeeded in determining the zero line of mechanical stress, finally correcting Galileo Galilei‘s incorrect results, and in 1826 he established the elastic modulus as a property of materials independent of the second moment of area. Navier is therefore often considered to be the founder of modern structural analysis. His major contribution, however, remains the Navier–Stokes equations (1822), central to fluid mechanics.]

The first investigation of any importance is that of the elastic line or elastica by James Bernoulli in 1705, in which the resistance of a bent rod is assumed to arise from the extension and contraction of its longitudinal filaments, and the equation of the curve assumed by the axis is formed. This equation practically involves the result that the resistance to bending is a couple proportional to the curvature of the rod when bent, a result which was assumed by Euler in his later treatment of the problems of the elastica, and of the vibrations of thin rods.

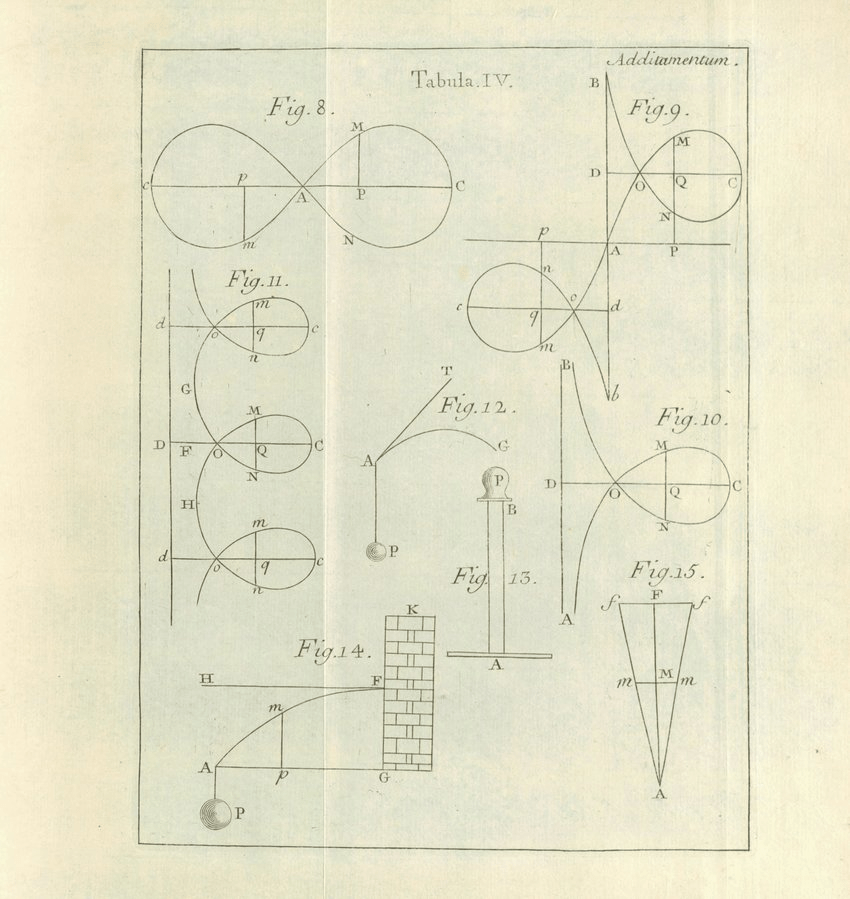

{The elastica from Euler Fig.11 in this figure should be rotated clockwise by 90º to get the form of a hydrostatic arch, from researchgate.}

[Jacob (James) Bernoulli[a] (1655-1705) was one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Swiss Bernoulli family…was an early proponent of Leibnizian calculus, which he made numerous contributions to; he was one of the founders of the calculus of variations. He also discovered the fundamental mathematical constant e. However, his most important contribution was in the field of probability, where he derived the first version of the law of large numbers in his work Ars Conjectandi.]

As soon as the notion of a flexural couple proportional to the curvature was established it could be noted that the work done in bending a rod is proportional to the square of the curvature.

Daniel Bernoulli suggested to Euler that the differential equation of the elastica could be found by making the integral of the square of the curvature taken along the rod a minimum… Euler, acting on this… was able to obtain the differential equation of the curve…

[Daniel Bernoulli 1700 – 1782) was also one of the many prominent mathematicians in the Bernoulli family. He is particularly remembered for his applications of mathematics to mechanics, especially fluid mechanics, and for his pioneering work in probability and statistics]

[Leonhard Euler (1707 – 1783) was a Swiss mathematician, physicist, astronomer, geographer, logician, and engineer who founded the studies of graph theory and topology and made pioneering and influential discoveries in analytic number theory, complex analysis, and infinitesimal calculus. He introduced much of modern mathematical terminology and notation, including the notion of a mathematical function. He is also known for his work in mechanics, fluid dynamics, optics, astronomy, and music theory. He is considered to be one of the greatest mathematicians of all time.]

Euler pointed out… that the rod, if of sufficient length and vertical when unstrained, may be bent by a weight attached to its upper end… [and was led] to assign the least length of a column in order that it may bend under its own or an applied weight. Lagrange followed and used his theory to determine the strongest form of column. These two… found [the] length which a column must attain to be bent by its own or an applied weight, and… that for shorter lengths it will be simply compressed, while for greater lengths it will be bent. These researches are the earliest in… elastic stability.

[Joseph-Louis Lagrange, comte de l’Empire (1736 – 1813) was an Italian-French mathematician and astronomer who made important contributions to all fields of analysis and number theory and to classical and celestial mechanics.]

In Euler‘s work on the elastica the rod is thought of as a line of particles which resists bending. {ie, the line exists with a length but has no other dimension, or thickness. This takes the idea proposed by Boscovich (see below) of dot points, centres of Force, and extends it to 2 dimensions. A place exists as a line, not a point. This is where Lewe can be seen in play. His work investigates this line, and the motion within} The theory of the flexure of beams of finite section was considered by Coulomb… [by investigating] the equation of equilibrium obtained by resolving horizontally the forces which act upon the part of the beam cut off by one of its normal sections, as well as of the equation of moments. He… thus… obtain[ed] the true position of the “neutral line,” or axis of equilibrium, and he also made a correct calculation of the moment of the elastic forces. His theory of beams is the most exact of those [that assume] the stress in a bent beam arises wholly from the extension and contraction of its longitudinal filaments, and… Hooke’s Law.

[Charles-Augustin de Coulomb (June 14, 1736 – August 23, 1806) was a French physicist. He is best known for developing Coulomb’s law, the definition of the electrostatic force of attraction and repulsion. The unit of charge, the coulomb, was named after him]

Coulomb was also the first to consider the resistance [although considered as non-elastic] of thin fibres to torsion… to which Saint-Venant refers under the name I’ancienne thiorie… Coulomb was [also] first to [consider] strain we now call shear, though he considered it in connexion with rupture only… when the shear [permanent set, not an elastic strain] of the material is greater than a certain limit.

Except Coulomb’s, the most important work of the period for the general mathematical theory is the physical discussion of elasticity by Thomas Young. …[Young,] besides defining his modulus of elasticity, was the first to consider shear as an elastic strain. He called it “detrusion,” and noticed that the elastic resistance of a body to shear, [as opposed to] its resistance to extension or contraction, are in general different; but he did not introduce a distinct modulus of rigidity to express resistance to shear. He defined “the modulus of elasticity of a substance” as “a column of the same substance capable of producing a pressure on its base which is to the weight causing a certain degree of compression, as the length of the substance is to the diminution of its length.” What we now call “Young’s modulus” is the weight of this column per unit of area of its base. This introduction of a definite physical concept, associated with the coefficient of elasticity which descends, as it were from a clear sky, on the reader of mathematical memoirs, marks an epoch in the history of the science.

[Thomas Young (1773 – 1829) was a British polymath who made notable contributions to the fields of vision, light, solid mechanics, energy, physiology, language, musical harmony, and Egyptology. Young has been described as “The Last Man Who Knew Everything“.[1] His work influenced that of William Herschel, Hermann von Helmholtz, James Clerk Maxwell, and Albert Einstein. Young is credited with establishing Christiaan Huygens’ wave theory of light, in contrast to the corpuscular theory of Isaac Newton.[2] Young’s work was subsequently supported by the work of Augustin-Jean Fresnel.[3]

During the first period in the history of our science (1638—1820) while these various investigations of special problems were being made, there was a cause at work which was to lead to wide generalizations. This cause was physical speculation concerning the constitution of bodies. {what is matter?} In the eighteenth century the Newtonian conception of material bodies, as made up of small parts which act upon each other by means of central forces, displaced the Cartesian conception of a plenum pervaded by “vortices.” Newton regarded his “molecules” as possessed of finite sizes and definite shapes, but his successors gradually simplified them into material points. The most definite speculation of this kind is that of Boscovich, for whom the material points were nothing but persistent centres of force. To this order of ideas belong Laplace‘s theory of capillarity and Poisson‘s first investigation of the equilibrium of an “elastic surface,” but for a long time no attempt seems to have been made to obtain general equations of motion and equilibrium of elastic solid bodies.

[Roger Joseph Boscovich (1711 – 1787) was a physicist, astronomer, mathematician, philosopher, diplomat, poet, theologian, Jesuit priest, and a polymath from the Republic of Ragusa.

We fashion our geometry on the properties of a straight line because that seems to us to be the simplest of all. But really all lines that are continuous and of a uniform nature are just as simple as one another. Another kind of mind which might form an equally clear mental perception of some property of any one of these curves, as we do of the congruence of a straight line, might believe these curves to be the simplest of all, and from that property of these curves build up the elements of a very different geometry, referring all other curves to that one, just as we compare them to a straight line. Indeed, these minds, if they noticed and formed an extremely clear perception of some property of, say, the parabola, would not seek, as our geometers do, to rectify the parabola, they would endeavor, if one may coin the expression, to parabolify the straight line]

[Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749 – 1827) was a French mathematician and astronomer, discoverer of the Laplace transform and Laplace’s equation.

“One sees, from this Essay, that the theory of probabilities is basically just common sense reduced to calculus; it makes one appreciate with exactness that which accurate minds feel with a sort of instinct, often without being able to account for it.”]

[Siméon-Denis Poisson (1781 – 1840) was a French mathematician, geometer, and physicist who specialized in applying mathematics to a wide variety of physics fields, including electricity, magnetism, hydrodynamics and celestial mechanics.

‘In many different fields, empirical phenomena appear to obey a certain general law, which can be called the Law of Large Numbers. This law states that the ratios of numbers derived from the observation of a very large number of similar events remain practically constant, provided that these events are governed partly by constant factors and partly by variable factors whose variations are irregular and do not cause a systematic change in a definite direction‘. Statement of Poisson’s law also known as the Law of Large Numbers (1837), as quoted by Richard Von Mises (1957). Probability, Statistics and Truth. Allen and Unwin. p. 104-105.

‘That which can affect our senses in any manner whatever, is termed matter‘. Introductory sentence of Siméon-Denis Poisson, translated by Henry Hickman Harte (1842). A Treatise of Mechanics. Longman and co. p. 1.

Poisson’s ratio is a measure of the Poisson effect, the phenomenon in which a material tends to expand in directions perpendicular to the direction of compression.]

At the end of the year 1820 the fruit of all the ingenuity expended on elastic problems might be summed up as—

- an inadequate theory of flexure,

- an erroneous theory of torsion,

- an unproved theory of the vibrations of bars and plates,

- and the definition of Young’s modulus.

But such an estimate would give a very wrong impression of the value of the older researches. The recognition of the distinction between shear and extension was a preliminary to a general theory of strain; the recognition of forces across the elements of a section of a beam, producing a resultant, was a step towards a theory of stress; the use of differential equations for the deflexion of a bent beam and the vibrations of bare and plates, was a foreshadowing of the employment of differential equations of displacement; the Newtonian conception of the constitution of bodies, combined with Hooke’s Law, offered means for the formation of such equations; and the generalization of the principle of virtual work [The work of a force acting on a particle as it moves along a displacement is different for different displacements. Among all the possible displacements that a particle may follow, called virtual displacements, one will minimize the action. This displacement is therefore the displacement followed by the particle according to the principle of least action. The work of a force on a particle along a virtual displacement is known as the virtual work.] in the Mécanique Analytique threw open a broad path to discovery in this as in every other branch of mathematical physics.

Physical Science had emerged from its incipient stages with definite methods of hypothesis and induction and of observation and deduction, with the clear aim to discover the laws by which phenomena are connected with each other, and with a fund of analytical processes of investigation. This was the hour for the production of general theories, and the men were not wanting.

In… 1821… Fresnel announced his conclusion that the observed facts in regard to the interference of polarised light could be explained only by the hypothesis of transverse vibrations. He showed how a medium consisting of “molecules ” connected by central forces might be expected to execute such vibrations and to transmit waves of the required type. Before the time of Young and Fresnel such examples of transverse waves as were known—waves on water, transverse vibrations of strings, bars, membranes and plates—were in no case examples of waves transmitted through a medium; and neither the supporters nor the opponents of the undulatory theory of light appear to have conceived of light waves otherwise than as “longitudinal ” waves of condensation and rarefaction, of the type rendered familiar by the transmission of sound.

[Augustin-Jean Fresnel (1788 – 1827) was a French civil engineer and physicist whose research in optics led to the almost unanimous acceptance of the wave theory of light, excluding any remnant of Newton‘s corpuscular theory, from the late 1830s until the end of the 19th century.]

The theory of elasticity, and, in particular, the problem of the transmission of waves through an elastic medium now attracted the attention of… Cauchy and Poisson—the former a discriminating supporter, the latter a sceptical critic of Fresnel‘s ideas. In the future the developments of the theory of elasticity were to be closely associated with the question of the propagation of light, and these developments arose in great part from the labours of these two savants.

[Augustin Louis Cauchy (1789 – 1857) was a French mathematician and physicist who made pioneering contributions to analysis. He was one of the first to state and prove theorems of calculus. He almost singlehandedly founded complex analysis and the study of permutation groups in abstract algebra. He was one of the most prominent mathematicians of the first half of the nineteenth century

… very often the laws derived by physicists from a large number of observations are not rigorous, but approximate. Augustin Louis Cauchy (1868). Sept leçons de physique. Bureau du Journal Les Mondes.

I am a Christian, that is, I believe in the divinity of Christ, as did Tycho Brahe, Copernicus, Descartes, Newton, Fermat, Leibniz, Pascal, Grimaldi, Euler, Guldin; Boscovich, Gerdil, as did all the great astronomers, physicist and geometricians of past ages. As translated by Julio Antonio Gonzalo (2008). The Intelligible Universe: An Overview of the Last Thirteen Billion Years. World Scientific. p. 301.]

By the Autumn of 1822 Cauchy had discovered most of the elements of the pure theory of elasticity. …[H]e had generalized the notion of hydrostatic pressure, and he had shown that the stress is expressible by means of six component stresses, and also by means of three purely normal tractions across a certain triad of planes which cut each other at right angles—the “principal planes of stress.”

[Cauchy] had shown also how the differential coefficients of the three components of displacement can be used to estimate the extension of every linear element of the material, and had expressed the state of strain near a point in terms of six components of strain {Lewe’s technique is to split the strain into 6 components}, and also in terms of the extensions of a certain triad of lines which are at right angles to each other—the “principal axes of strain.”

[Cauchy] had determined the equations of motion (or equilibrium) by which the stress-components we connected with the forces that are distributed through the volume and with the kinetic reactions. By means of relations between stress-components and strain-components, he had eliminated the stress-components from the equations of motion and equilibrium, and had arrived at equations in terms of the displacements.

Cauchy obtained his stress-strain relations for isotropic materials by means of two assumptions, viz. : (1) that the relations in question are linear, (2) that the principal planes of stress are normal to the principal axes of strain.

[Cauchy’s] equations… are those which are now admitted for isotropic solid bodies. The methods used in these investigations are quite different from… Navier‘s… no use is made of the hypothesis of material points and central forces. …Navier’s equations contain a single constant to express the elastic behaviour of a body, while Cauchy’s contain two such constants.

At a later date Cauchy extended his theory to the case of crystalline bodies, and he then made use of the hypothesis of material points between which there are forces of attraction or repulsion.

Clausius criticized the restrictive conditions which Cauchy imposed upon the arrangement of his material points, but he argued that these conditions are not necessary for the deduction of Cauchy’s equations.

[Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (1822 –1888) was a German physicist and mathematician. He is considered one of the founders of the science of thermodynamics. His most important paper, On the Moving Force of Heat (1850) was first to declare the second law of thermodynamics. He introduced the concept of entropy in 1865, and the virial theorem for heat in 1870.

If for the entire universe we conceive the same magnitude to be determined, consistently and with due regard to all circumstances, which for a single body I have called entropy, and if at the same time we introduce the other and simpler conception of energy, we may express in the following manner the fundamental laws of the universe which correspond to the two fundamental theorems of the mechanical theory of heat.

1. The energy of the universe is constant.

2. The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum.

Ninth Memoir. On Several Convenient Forms of the Fundamental Equations of the Mechanical Theory of Heat.]

[Poisson‘s] April, 1828… memoir is very remarkable… like Cauchy, [he] first obtains the equations of equilibrium in terms of stress-components, and then estimates the traction across any plane resulting from the “intermolecular” forces. The expressions… involve summations with respect to all the “molecules,” situated within the region of “molecular” activity of a given one. Poisson… assumes… summations with respect to angular space about the given “molecule,” but not… with respect to distance… The equations of equilibrium and motion of isotropic elastic solids… thus obtained are identical with Navier‘s.

Poisson assumed that the irregular action of the nearer molecules may be neglected, in comparison with the action of the remoter ones, which is regular. This assumption is the text upon which Stokes afterwards founded his criticism of Poisson. As we have seen, Cauchy arrived at Poisson’s results by the aid of a different assumption. Clausius held that both Poisson’s and Cauchy’s methods could be presented in unexceptionable forms.

[Sir George Gabriel Stokes, 1st Baronet FRS ( 1819 – 1903) was a mathematician and physicist, who made important contributions to fluid dynamics (including the Navier–Stokes equations), optics, and mathematical physics (including Stokes’ theorem).

Note the Reynolds number was named by Arnold Sommerfeld in 1908[3] after Osborne Reynolds (1842–1912), who popularized its use in 1883 but the concept was introduced by George Stokes in 1851. In fluid dynamics, the Reynolds number (Re) is a dimensionless quantity that helps predict fluid flow patterns in different situations by measuring the ratio between inertial and viscous forces. At low Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be dominated by laminar (sheet-like) flow, while at high Reynolds numbers, flows tend to be turbulent. The turbulence results from differences in the fluid’s speed and direction, which may sometimes intersect or even move counter to the overall direction of the flow (eddy currents). These eddy currents begin to churn the flow, using up energy in the process, which for liquids increases the chances of cavitation.]

The revolution which Green effected in the elements of the theory is comparable in importance with that produced by Navier’s discovery of the general equations. Starting from what is now called the Principle of the Conservation of Energy he propounded a new method of obtaining these equations.

[George Green (1793 – 1841) was a British mathematical physicist, who wrote An Essay on the Application of Mathematical Analysis to the Theories of Electricity and Magnetism which introduced several important concepts, among them a theorem similar to modern Green’s theorem, the idea of potential functions as currently used in physics, and the concept of what are now called Green’s functions

‘The properties of bodies were investigated by several distinguished French mathematicians on the hypothesis that they are systems of molecules in equilibrium. The somewhat unsatisfactory nature of the results… produced… a reaction in favour of the opposite method of treating bodies as if they were… continuous. This method, in the hands of Green, Stokes, and others, has led to results the value of which does not at all depend on what theory we adopt as to the ultimate constitution of bodies‘

James Clerk Maxwell, “Introductory Lecture on Experimental Physics,” The Scientific Papers of James Clerk Maxwell (1890) Vol.2]

[Green] stated his principle and method in the following words:—

“In whatever way the elements of any material system may act upon each other, if all the internal forces exerted be multiplied by the elements of their respective directions, the total sum for any assigned portion of the mass will always be the exact differential of some function. But this function being known, we can immediately apply the general method given in the Mécanique Analytique, and which appears to be more especially applicable to problems that relate to the motions of systems composed of an immense number of particles mutually acting upon each other. One of the advantages of this method, of great importance, is that we are necessarily led by the mere process of the calculation, and with little care on our part, to all the equations and conditions which are requisite and sufficient for the complete solution of any problem to which it may be applied.”

The function here spoken of, with its sign changed, is the potential energy of the strained elastic body per unit of volume, expressed in terms of the components of strain; and the differential coefficients of the function, with respect to the components of strain, are the components of stress. Green supposed the function to be capable of being expanded in powers and products of the components of strain. He therefore arranged it as a sum of homogeneous functions of these quantities of the first, second and higher degrees. Of these terms, the first must be absent, as the potential energy must be a true minimum when the body is unstrained; and, as the strains are all small, the second term alone will be of importance. From this principle Green deduced the equations of Elasticity, containing in the general case 21 constants. In the case of isotropy there are two constants, and the equations are the same as those of Cauchy’s first memoir.

Lord Kelvin has based the argument for the existence of Green’s strain-energy-function on the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics. From these laws he deduced the result that, when a solid body is strained without alteration of temperature, the components of stress are the differential coefficients of a function of the components of strain with respect to these components severally. The same result can be proved to hold when the strain is effected so quickly that no heat is gained or lost by any part of the body.

Poisson‘s theory leads to the conclusions that the resistance of a body to compression by pressure uniform all round it is two-thirds of the Young’s modulus of the material, and that the resistance to shearing is two-fifths of the Young’s modulus. He noted a result equivalent to the first of these, and the second is virtually contained in his theory of the torsional vibrations of a bar.

The observation that resistance to compression and resistance to shearing are the two fundamental kinds of elastic resistance in isotropic bodies was made by Stokes, and he introduced definitely the two principal moduluses of elasticity… the “modulus of compression” and the “rigidity,” as they are now called.

From Hooke’s Law and from considerations of symmetry [Stokes] concluded that pressure equal in all directions round a point is attended by a proportional compression without shear, and that shearing stress is attended by a corresponding proportional shearing strain.

As an experimental basis for Hooke’s Law [Stokes] cited the fact that bodies admit of being thrown into states of isochronous vibration.

By a method analogous to that of Cauchy‘s first memoir, but resting on the above-stated experimental basis, [Stokes] deduced the equations with two constants which had been given by Cauchy and Green. Having regard to the varying degrees in which different classes of bodies—liquids, soft solids, hard solids—resist compression and distortion, he refused to accept the conclusion from Poisson’s theory that the modulus of compression has to the rigidity the ratio 5:3. He pointed out that, if the ratio of these moduluses could be regarded as infinite, the ratio of the velocities of “longitudinal ” and ” transverse ” waves would also be infinite, and then, as Green had already shown, the application of the theory to optics would be facilitated.

The hypothesis of material points and central forces does not now hold the field. …Of much greater importance have been the development of the atomic theory {here Lewe provides the detail of the Nuclear Force} in Chemistry and of statistical molecular theories in Physics, the growth of the doctrine of energy, the discovery of electric radiation. It is now recognized that a theory of atoms must be part of a theory of the æther, and that the confidence which was once felt in the hypothesis of central forces between material points was premature. To determine the laws of the elasticity of solid bodies without knowing the nature of the æthereal medium or the nature of the atoms, we can only invoke the known laws of energy as was done by Green and Lord Kelvin; and we may place the theory on a firm basis if we appeal to experiment to support the statement that, within a certain range of strain, the strain-energy-function is a quadratic function of the components of strain, instead of relying, as Green did, upon an expansion of the function in series.

The problem of curved plates or shells was first attacked from the point of view of the general equations of Elasticity by H. Aron. He expressed the geometry of the middle-surface by means of two parameters after the manner of Gauss, and he adapted to the problem the method which Clebsch had used for plates. He arrived at an expression for the potential energy of the strained shell which is of the same form as that obtained by Kirchhoff for plates, but the quantities that define the curvature of the middle-surface were replaced by the differences of their values in the strained and unstrained states.

{Hermann Aron (1845 – 1913) was a German researcher of electrical engineering. MR-Wikipedia makes no reference to his work on Elasticity below, and yet this is identified by Love as a key work}

Reference: Hermann Aron, “Das Gleichgewicht und die Bewegung einer Unendlich Dunnen, Beliebig Gekrummten, Elastischen Schale” [“The equilibrium and the motion of an infinitely thin, elastic curved shell”], Journal fiir Reine und Ange. Math (1874) also see 1873 Crelle, Journ Math 78 (1874) pp. 136-174, as referenced in the Catalogue of Scientific Papers, Vol. 9, p. 71, Royal Society.

E. Mathieu adapted to the problem [of curved plates or shells ] the method which Poisson had used for plates. He observed that the modes of vibration possible to a shell do not fall into classes characterized respectively by normal and tangential displacements, and he adopted equations of motion that could be deduced from Aron‘s formula for the potential energy by retaining the terms that depend on the stretching of the middle-surface only.

[Émile Léonard Mathieu (1835 -1890) was a French mathematician.[1] He is known for his work in group theory and mathematical physics. He has given his name to the Mathieu functions, Mathieu groups and Mathieu transformation. He authored a treatise of mathematical physics in 6 volumes. Volume 1 is an exposition of the techniques to solve the differential equations of mathematical physics, and contains an account of the applications of Mathieu functions to electrostatics. Volume 2 deals with capillarity. Volumes 3 and 4 deal with electrostatics and magnetostatics. Volume 5 deals with electrodynamics, and volume 6 with elasticity. The asteroid 27947 Emilemathieu was named in his honour.]

Lord Rayleigh… concluded from physical reasoning that the middle-surface of a vibrating shell {the inertial frame of reference expressed as line} remains unstretched, and determined the character of the displacement of a point of the middle-surface in accordance with this condition. The direct application of the Kirchhoff-Gehring method led to a formula for the potential energy of the same form as Aron‘s and to equations of motion and boundary conditions which were difficult to reconcile with Lord Rayleigh’s theory. Later investigations have shown that the extensional strain which was thus proved to be a necessary concomitant of the vibrations may be practically confined to a narrow region near the edge of the shell, but that, in this region, it may be so adjusted as to secure the satisfaction of the boundary conditions while the greater part of the shell vibrates according to Lord Rayleigh’s type.

[John William Strutt, 3rd Baron Rayleigh, OM, PC, FRS (1842 – 1919) was a British mathematician and physicist who made extensive contributions to science.

Rayleigh provided the first theoretical treatment of the elastic scattering of light by particles much smaller than the light’s wavelength, a phenomenon now known as “Rayleigh scattering“, which notably explains why the sky is blue. He studied and described transverse surface waves in solids, now known as “Rayleigh waves“. He contributed extensively to fluid dynamics, with concepts such as the Rayleigh number (a dimensionless number associated with natural convection), Rayleigh flow, the Rayleigh–Taylor instability, and Rayleigh’s criterion for the stability of Taylor–Couette flow. He also formulated the circulation theory of aerodynamic lift. In optics, Rayleigh proposed a well-known criterion for angular resolution. His derivation of the Rayleigh–Jeans law for classical black-body radiation later played an important role in the birth of quantum mechanics (see Ultraviolet catastrophe). Rayleigh’s textbook The Theory of Sound (1877) is still used today by acousticians and engineers.]

Whenever very thin rods or plates are employed in constructions it becomes necessary to consider the possibility of buckling, and thus there arises the general problem of elastic stability. [T]he first investigations… of this kind were made by Euler and Lagrange. …In all [isolated problems] two modes of equilibrium with the same type of external forces are possible, and the ordinary proof of the determinacy of the solution of the equations of Elasticity is defective.